Home » 2014

Yearly Archives: 2014

Collecting Information about Infants and Toddlers A Smorgasbord of Choices

A primary role of an early interventionist is to document the development of a young child. We collect this type of information for a variety of reasons, including to: determine skill level, determine strengths, determine patterns of development, etc. We collect information in five primary developmental domains: adaptive, cognitive, communication, motor, and social-emotional. We use assessment tools, evaluation tests, screening procedures to make these determinations. Using procedures that are structured helps us feel confident that the differences we may see are accurate. Assessing children early is key to the identification of delays and referral to services and supports that may be of help to promote functional participation of the child in everyday activities.

A primary role of an early interventionist is to document the development of a young child. We collect this type of information for a variety of reasons, including to: determine skill level, determine strengths, determine patterns of development, etc. We collect information in five primary developmental domains: adaptive, cognitive, communication, motor, and social-emotional. We use assessment tools, evaluation tests, screening procedures to make these determinations. Using procedures that are structured helps us feel confident that the differences we may see are accurate. Assessing children early is key to the identification of delays and referral to services and supports that may be of help to promote functional participation of the child in everyday activities.

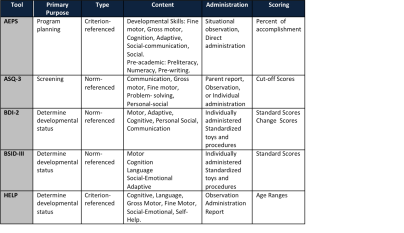

However, there are so many tools and tests available that all appear to do the same thing. SO— “What’s the difference?!” This blog will outline the basic differences among five commonly used early intervention assessments: Assessment, Evaluation, And Programming System for Infants and Children-2nd Ed. (AEPS-2), Ages and Stages Questionnaires, 3rd Ed. (ASQ-3), Battelle Development Inventory, 2nd Ed.(BDI-2), Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-3rd Ed.(BSID-III), and the Hawaii Early Learning Profile (HELP).

Each of these tools collects information about the child’s status in the five major developmental domains: motor, cognition, communication, social-emotional, and adaptive. Although these tools are similar there are some clear differences that indicate the strengths of each one. AEPS is widely regarded as one of the best curriculum-based, criterion-referenced tools in the early childhood field. ASQ-3 is considered an accurate, family-friendly way to screen children for developmental delays between one month and 5½ years. The BDI-2 and the BSID-III are norm-referenced standardized tools that determine if a child is delayed in comparison to his or her age group peers. The BDI-2 has also been shown to be useful to monitor change in development over time.

The following chart describes each of these five tools on five main elements of test/tool construction: purpose, type, content, administration and scoring.

The psychometric qualities of a tool are also important to consider, because reliability and validity are important to help a practitioner determine which tools will give them the most accurate information for their purposes. Reliability provides information on consistency of each assessment tool while validity refers to how well a test measures what it is purported to measure.

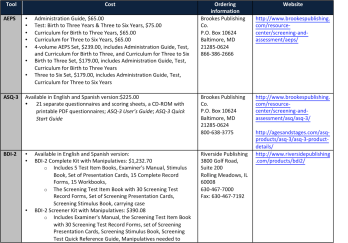

Pricing and availability are other issues to take into account when a practitioner tries to choose the right assessment. Please see the chart below to find the cost, ordering information and website for each tool.

—

Meng Lyu

East China Normal University

Children with Disability in the United Arab Emirates and the Services they Receive

The author of this post is a visiting scholar with the Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development and a student with the Georgetown University Certificate in Early Intervention Program

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) one of the Arabic Countries of the Middle East is comprised of seven emirates. Situated on the Arabian Gulf, east of Saudi Arabia and north of Oman, the UAE has a long history of local tribal lifestyle and of later European influences. The country has dramatically emerged into the mainstream of modernism over the past 42 years. The economy is driven by oil and gas and recently tourism. In 1951, the Trucial States Council was formed, bringing all the leaders of the various groups throughout the region together. Seven emirates, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ras-Al-Kahaimah, Fujairah, Umm Al Qaiwain, Ajman, joined together forming the United Arab Emirates in 1971.

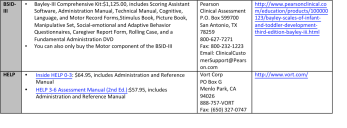

The major religion of the country is Islam. Ninety-six percent of the population is Muslim and the rest are Christian or Hindu . The population of the UAE is approximately 8 million people, of which only 20-22 percent are Emirati citizens. Most of the population is made up of expatriates, about 50% of whom are from the Indian subcontinent. The population as a high percentage of young people (Table 1). According to the World Health Organization approximately 11 percent of the UAE population has a disability. This percentage is consistent with what the WHO projects is the world’s population of people with disabilities.

Table 1

The Government of the UAE is committed to the welfare of children. Children who are citizens receive free health care and education. The standards of health care are considered to be generally high in the United Arab Emirates. During the strong economic years the government spent a significant amount of money on health care. According to the government, total expenditures on health care from 1996 to 2003 were US $436 million.

The UAE is interested in developing services for people with disabilities. The UAE Disability Act (Federal Law No. 29/2006) was passed in 2006 to protect the rights of people with disabilities. This law stipulates that UAE nationals with disabilities have the same rights to work and occupy public positions. In addition, the UAE ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on the March 19, 2010.

In March 2014, HH Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE, in his capacity as the Ruler of Dubai, issued Law No. (2) of 2014 “to protect the rights of people with disabilities in the emirate of Dubai”. The law supports Federal Law No. (29) concerning the rights of people with disabilities, and supports providing high-quality medical care and social services, boosts public awareness of people with disabilities, contributes to integrating people with disabilities into society, and reaffirms their participation in social development .

Services for people with disabilities are offered primarily in three types of programs:

o Governmental Centers, which are run by the federal, or local government (state), offering free services especially to the citizens .

o Semi-governmental Centers, usually organized by non-profit charitable organizations, offering free or semi free services.

o Private centers or schools or rehabilitation clinics which require a fee or payment for services.

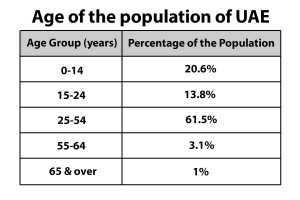

Services offered to people with disabilities according to age group include the following (Table 2) :

Table 2

Each emirate (state) has its own rules and regulations regarding programs for people with disabilities. The emirate of Sharjah has a long history of concern for people with disabilities. Sharjah City for Humanitarian Services (SCHS ) is a large, local, non-profit organization founded in 1979 as a branch of the Arab Family Organization in the Gulf region. The purpose of the Arab Family Organization is to support Arab families and provide needed social services. SCHS is considered the first institute in UAE to provide specialized services to persons with disabilities.

The vision of the SCHS is to be a leader in advocacy, inclusion, and empowerment for persons with disabilities in the United Arab Emirates and the Arab world. The mission is to provide services in early intervention, community outreach, education, rehabilitation, and job placement for people with disabilities assisting them to become independent, self-reliant members of society.

Sharjah City for Humanitarian Services (SCHS) has almost 500 employees, serving around 3000 persons with disability yearly. People served include all age groups. What is unique is that the SCHS serves all residents, including non-emirates. SCHS has three branches in the Emirate of Sharjah. SCHS offers a variety of programs via specialized centers, departments, and schools covering several programs:

• Al Amal school for the students with hearing Impairments and Al Amal Kindergarten for students with hearing Impairments , ( nursery to secondary level (preschool to grade 12).

• Al Wafa Schools for developmental training for students with intellectual disabilities from age 5 years and above.

• Sharjah Autism center for children with autism from age 5 years and above.

• Early intervention center for children from birth till age 5 years.

• Physical and Occupational Therapy Dept. for children with motor and sensory impairments from 0-18 years.

• Vocational Rehabilitation and Training Dept. from age 15 years and above.

• Sharjah City Audiology Center for all people with hearing impairments (hearing test and follow up) all age group.

• There is also a unit for people with visual impairment offering the services for all age groups.

As mentioned there is three branches of SCHS in Sharjah having the same mentioned facilities and programs organized regionally throughout Sharjah:

1. SCHS Middle region (Al Thiad branch).

2. SCHS East region (Khorfakkan Branch).

3. SCHS East region (Kalbaa branch).

One of the most important centers of SCHS is the early intervention center (EIC ) established in 1992 servicing children from birth till 5 years of age. This center is the first one in the region, to offer services to young children, their families and the community. The Center has a variety of departments and facilities:

o Social services department

o Family counseling and training department including home based services

o Speech-language therapy department

o Educational department including a preschool program for children 3-5 years

o Visual impairment department all ages

o Physical and Occupational Therapy department

o AVT and Audiology test department for all ages

o Psychology department

There is also a screening program at the local nursery and preschool programs, and an inclusion follow up program with the local schools .

The Center serves about 350 children annually and has served around 2700 children since official opening in 1992. Each year 120 new children are enrolled in the center services.

Finally the SCHS is looking to influence the community’s attitude throughout Sharjah to guarantee real integration and inclusion for people with disabilities in all aspects of life (Educational, Medical, Social) .

Islam sees disability as morally neutral. It is seen neither as a blessing nor as a curse. Clearly, disability is therefore accepted as being an inevitable part of the human condition. It is simply a fact of life which has to be addressed appropriately by the society of the day, thus, people with disabilities are given an opportunity for independency. Also, federal law 29/2006 of the UAE provides Emirates with disabilities the right to be part of the society. However, implementing federal law 29/2006 continues to be challenging.

Although there is interest in integrated, inclusionary services most services in the UAE continue to be delivered through centers for special needs. Additionally, the UAE lacks schools that accept children with disability without restrictions. There continues to be a lack of services and service providers to serve all children with disabilities even using segregated, isolated programs, especially in early intervention. Creating appropriate early childhood services using contemporary evidence based programs for children birth to three needs to be emphasized.

Resources

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_in_the_United_Arab_Emirates

2. http://dubai.ae/en/Lists/Topics/DispForm.aspx?ID=15&category=Home

3. http://schs.ae/aboutus.aspx

4. http://www.disabled-world.com/disability/statistics/

5. Bradshaw, K., Tennant, L., & Lydiatt, S. (2004). Special education in the United Arab Emirates: Anxieties, attitudes, and aspirations. International Journal of Special Education (19)1, 49-55 .

6. http://www.enmcr.net/site/assets/files/1382/children_s_rights_in_uae_-_fatma_beshir.pdf

7. Dr. Christopher Reynolds ; Federal Law 29 – The Implications for Private Schools in the UAE http://who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/technical_appendices.pdf

8. https://www.swisslife.com/content/dam/id_corporateclients/downloads/ebrm/UAE.pdf

9. http://www.escwa.un.org/popin/members/uae.pdf

10. http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/united-arab-emirates-population/

11. http://www.expatwoman.com/abudhabi/monthly_abudhabi_faqs_Special_Needs_Resources_and_Support_In_The_UAE_9261.aspx

Mohammad Yousef

GU Certificate in Early Intervention (2015)

Physical Therapists, Sharjah City for Humanitarian Services (SCHS )

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome – Preventable but Persistent

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder (FASD) affects an estimated 40,000 infants each year (SAMSHA, 2003). FASD is an umbrella term describing a range of characteristics that can occur in children prenatally exposed to alcohol. The characteristics may include physical,

behavioral, and/or learning disabilities that last a lifetime. According to National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (NOFAS, 2014) FASD includes 4 distinct syndromes associated with prenatal alcohol exposure.

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), Partial

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (PFAS), Neurobehavioral Disorder

- Associated with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure (ND-PAE), and

- Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND) are the

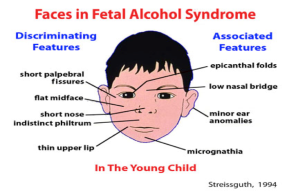

FASD is characterized by unique physical features and a variety of problems that can impact learning and social participation. Physical features of FASD are depicted in the figure:

Other characteristics of the syndrome may include: intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities, poor impulse control, language deficits, memory deficits, and poor social adaptability. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome is the leading cause of intellectual disabilities in children (Shapiro & Batshaw, 2013) yet it is 100% preventable. It is unclear how much alcohol is needed to affect a fetus. According to the CDC, the U.S. Surgeon General, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, there is no known safe amount of alcohol to drink while pregnant. There is also no safe time during pregnancy to drink and no safe kind of alcohol. Research indicates that even drinking small amounts of alcohol while pregnant can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, or sudden infant death syndrome.

If ways can be found to curb the intake of alcohol among pregnant women, a huge number of children would not have the live with the negative consequences alcohol exposure. Services and supports are needed and necessary to prevent women from drinking while pregnant. Prevention of drinking during pregnancy, especially during the critical first few months is challenging for a host of reasons. Alcohol consumption in pregnant women is not a single issue.

A study done in Washington State among women who had given birth to children with FASD provides insight into the intricacies of this issue. Intersecting social challenges include mental health disorders, physical and/or psychological abuse, and lack of education. Ninety-six percent of women who gave birth to a child with FAS had at least one mental health disorder, 95% had a history of sexual or physical abuse, 61% had less than a high school education, 25% had some college education, 77% had an unplanned pregnancy, and of that group 81% did not use birth control although most of the women ( 92%) wanted some form of birth control, and 59% had an annual gross household income of less than $10,000 (Grant, et al, 2009).

Unlike other characteristics of vulnerable populations, alcohol consumption cuts across ethnic, racial, and economic lines. Perreira and Cortes (2006) found that all segments of the population admitted to drinking alcohol while pregnant: 17% White, non-Hispanic, 9.7% Black, non-Hispanic, and 6.4% Hispanic. Almost 12 % of those who said they were born in the United States drank alcohol during pregnancy, as opposed to 8.2 percent who said they were foreign born. It is evident that this issue is persistent throughout the country and that there is not a specific demographic which can be targeted to address the problem. Additionally, as demonstrated by the findings from Washington state alcohol consumption in pregnant women may be symptomatic of much more complicated issues that have far and long reaching effects.

Deciding where to begin to address the cause of the problem is difficult and complex. Do organizations first target the poverty, the mental illness, the maltreatment, the low maternal education, the lack of access to birth control, or the lack of prenatal care? Thus far, policy has focused not on the mother but on the child, often taking the child out of the home, as is evidenced by the overwhelming number of children in the foster care system who have FAS. Children in foster care are 10-15 times more likely to be affected by prenatal alcohol exposure than other children (FASD Center for Excellence, 2007). The most notable prevention measure is the FDA regulation that all alcohol products contain a warning label that alcohol can damage a fetus. Additionally, there are some public relation campaigns and public service announcements targeting high risk populations.

By framing the use of alcohol in pregnant women as a symptom of a larger issue, the conversation regarding policy could shift away from simply putting warning labels on alcoholic beverages and taking the child out of the home to policies that address the complexity of the problem and the intersecting needs of the mother. Prevention is obviously a key component of any policy or program created to address this problem. Nurse practitioner and gynecologists/ obstetricians training should include recognition of alcohol use, anticipatory guidance on the effects of alcohol consumption while pregnant, and recognizing and supporting women with mental health concerns, domestic violence, social service needs, etc. Most importantly, treatment could be determined by recognizing that the pregnant woman who is drinking may have complex health and social service needs as opposed to a “drinking problem”. This same perspective could be used to inform decisions regarding the child after it is born. Indeed, if the child needs to be taken out of the home, efforts could be made to also treat the mother for the larger issue of her alcohol or substance abuse. Lastly, because there is such a high percentage of children with alcohol related disabilities in foster care, it is also important to train foster parents on how best to support the child. By doing this, the child and the foster family are given an opportunity to develop a close relationship and experience success for the child. Dealing with alcohol related disabilities is hard for any family and thus support and knowledge surrounding the disability is key.

FASD is 100 % preventable. However, due to a variety of reasons and the myriad of complex interrelated issues, the likelihood of eliminating developmental disabilities due to alcohol is slim. Policies can, however, begin to address the interrelated issues of the pregnant woman by viewing her alcohol consumption as a symptom and not the root issue. Additionally, foster families can be better educated about the support needed for children diagnosed with FAS. The disabilities caused by prenatal alcohol consumption are serious and need to be taken as such. The reasons and issues surrounding the pregnant woman’s drinking are also serious and need to be taken as such.

References

- Grant T.M., Huggins, .J.E, Sampson, .P.D, Ernst, .C.C, Barr, .H.M., Streissguth, A.P.(2009). Alcohol use before and during pregnancy in western Washington, 1989-2004: Implications for the prevention of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 200(3): 278.e:1-8

- National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. (2014). FASD: What Everyone Should Know. Available from:http://www.nofas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Fact-sheet-what-everyone-should-know.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014). About FASD. Available from http://fasdcenter.samhsa.gov/aboutUs/aboutFASD.aspx

- Perreira, K. & Cortes, K. (2006). Race/ethnicity and nativity differences in alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health, 96(9), 1629-1636. Retrieved online at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.proxy.lib.csus.edu/pmc/articles/PMC1551957/.

- Phares, T., Morrow, B., Lansky, A., Barfield, W., Prince, C., Marchi, K., Braveman, P., William SAMSHA, 2003

- Shapiro, B. & Batshaw, M. (2013). Developmental Delay and Intellectual Disabilities. In M. L. Batshaw, N. J. Roizen, & G.R. Lotrecchiano, G.R. (Eds.), Children with disabilities. pp. 291-306. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

— Sophie Siebach

Georgetown University College, 2015

The Intersection of Poverty and Disability: What Does These Mean for Early Intervention

Image Source: Washington Post

Statistics show that poverty and disability are deeply intertwined. Nationally, 28 percent of children with disabilities fall below the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), compared to only 16 percent of children without disabilities (Emerson, 2007). This relationship is bidirectional, meaning that experiencing the environmental and psychosocial hazards that often accompany poverty increases the risk of disability, and the direct and indirect costs of having a disability increase the likelihood of falling into poverty, or at least of experiencing material hardship. These risk factors accumulate and interact over time; thus it is essential to intervene as early as possible in order to maximize positive outcomes for children with disabilities who have additional vulnerabilities such as being in poverty.

Research shows that the effectiveness of early intervention (EI) in such vulnerable populations is substantial (Long, 2013). The purpose of EI is to support families in their care of their children to facilitate the child’s participation and sense of membership in his or her family and community (Long, 2013). Many early interventionists follow the biomedical model, which focuses on managing or eradicating symptoms in “patients” rather than looking at a person and his or her capabilities and limitations within a social and environmental context (Halfon, Houtrow, Larson, & Newacheck, 2012). It would be far more beneficial, however, to approach children with disabilities and their families, especially those who experience additional vulnerabilities such as poverty, with a more family-centered approach. Before interacting with vulnerable families, early interventionists should consider their approach to early intervention, what they know about families that could influence their interactions, and what they should provide for them, given their needs and limitations.

Early interventionist’s use of an ecological approach will increase the likelihood that they will incorporate a systems perspective based on a strengths based, relationship, taking into account the life course of the child and family. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems approach posits that children develop in a system of nested environments, from their family and child care experiences (microsystems) to larger societal and cultural values and laws (macrosystem), and that these systems interact dynamically and change over time (Zajicek-Farber, 2013). From this perspective, the goal of intervention is not just to manage symptoms, but to improve the child’s social, physical, and psychological functioning within the contexts or environments he or she is expected to participate in. Using a relationship- and strengths-based approach means that early interventionists need to first develop a trusting, collaborative relationship with children and families, and to focus on their strengths (rather than limitations) that might be used as resources in helping to improve the child’s functioning and quality of life.

From a life course perspective, the goal of EI is to improve functioning and quality of life not just for children with disabilities in the moment, but to look ahead and anticipate needs across the lifespan so as children transition to and experience adulthood, they can maintain these improvements throughout their lives (Long, 2013). This is especially important when interacting with families because many have worries, fears, and questions about their children’s futures and what they will look like. Additionally, a lot of supports fall away as children with disabilities transition to adulthood, so it is important to look forward and prepare for the future very early on. Interacting with families in poverty in particular (who likely experience resource limitations and lack of information) from a life course approach could have further benefits for children because it impresses on parents the importance of each visit and each component of the intervention, and how every facet is necessary to lead to benefits for their children in the long term.

Before interacting with families in poverty or with other vulnerabilities, early interventionists should know what cultural beliefs, coping styles, priorities, strengths, and limitations families face on a regular basis. Cultural beliefs shape families’ relationships, behaviors, parenting practices, trust of professionals, and how they feel they can influence their children’s development. Early interventionists should pay particular attention to potential limitations and additional stressors that a family experiences. Strength-based interactions provide flexibility that may be necessary to provide the support needed to meet family needs.

When interacting with children and families with particular vulnerabilities, such as being in poverty, early interventionists should be particularly careful to be culturally sensitive and appropriate, sensitive to limitations, flexible, responsive, and understanding. All communications (both verbal and written) should be in the family’s preferred language, and should be in terms that are easy for families to understand and not riddled with technical jargon. Early interventionists should also be sure to share as much information as necessary to help families make informed decisions. Professionals should be sure to answer any questions that families have in a responsive, sensitive, and thorough way.

Best practice early intervention include establishing a collaborative partnership with families based on their strengths. Early intervention should empower families by informing them in a culturally appropriate and sensitive way and by modeling for them practices in which they can engage with their child on their own to promote his or her positive development. For vulnerable families in particular, early interventionists should be sure to connect them with community resources that will promote positive development, including transportation, health services, and assistance programs such as welfare, TANF, and WIC. It is especially important that professionals emphasize and facilitate the availability of these services because many families in poverty are not informed about programs for which they are eligible that could improve quality of life for themselves and their children. Professionals should also identify social supports that parents have and help them seek additional ones through support groups, mental health services, and other programs, because these parents are more likely to feel isolated and have mental health issues that could hinder the well-being of themselves and their children (Zajicek-Farber, 2013). Connecting families with these resources augments moderating and protective factors for children with disabilities who are at high risk because of the interaction between poverty and disability.

Overall, early interventionists should be respectful of children and families with vulnerabilities (especially being in poverty, which is associated with myriad other risks) and their desires, priorities, goals, limitations, and ultimate decisions. They should be cognizant of how the way they approach, think about, and interact with vulnerable families influences the course of the early intervention and thus the outcomes of the child with disabilities. Thus, early interventionists should make concerted efforts provide services that are family-centered, focusing on the child, in context, and across his or her lifespan, and his or her family.

References

Emerson, E. (2007). Poverty and people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 107-113.

Halfon, N., Houtrow, A., Larson, K., & Newacheck, P.W. (2012). The changing landscape of disability in childhood. The Future of Children, 22 (1), 13-42.

Long, T. (2013). Early Intervention. In M. L. Batshaw, N. J. Roizen, & G.R. Lotrecchiano, G.R. (Eds.), Children with disabilities. pp. 547-557. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

Zajicek-Farber, M. (2013). Caring and Coping: Helping the Family of a Child with a Disability. In M. L. Batshaw, N. J. Roizen, & G.R. Lotrecchiano, G.R. (Eds.), Children with disabilities. pp. 757-672. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

Shannon Reilly

Georgetown University,

College, Class of 2015

Practice Makes Perfect, But How?

How should young children practice new skills? How much practice is enough? How long should children practice? Karen Adolph, PhD, a developmental psychologist at New York University, has conducted numerous studies examining the development of locomotion in infants, how much practice is needed to become a competent walker, and what other factors influence the development of locomotion. Recently, Dr. Adolph and her team observed infants as they played freely under caregivers’ supervision in a laboratory playroom. The researchers compared the movement patterns of experienced crawlers and new walkers to gain insight into the development of locomotion. The authors found that, as expected, walking patterns improve with age. They also found that infants took about 14,000 steps a day, traveled the length of 46 football fields, and fell 100 times. That’s a lot of practice and butt bumps!

They also found that the infants were not in constant motion. Rather, they walked in short bursts that were separated by longer, stationary periods. This short burst of movement finding is consistent with motor learning research in older children and adults. Motor learning research has long suggested that effective practice conditions t allow for short practice periods with longer rest intervals. Intermittent rest periods allow for the body to recover from fatigue, renew motivation, and to consolidate learning.

As early interventionists, we know that children need a lot of practice in order to learn new skills. BUT—–14, 000 steps a day are A LOT! Does that surprise you? How do you coach families to increase practice opportunities? What questions do you ask families to find out how much a child is currently practicing a skill? What strategies have you used to help families increase a child’s opportunities to practice a skill?

Adolph, K.E., Cole, W.G., Komati, M., et al. (2012). How do you learn to walk? Thousands of steps and dozens of falls per day, Psychological Science, 23, pp 1387-1394.

For more information on Dr. Adolph’s work visit her website:

http://psych.nyu.edu/adolph/index.php?page=home

–Jamie Holloway

Facts about the Primary Service Provider (PSP) Model

A child is learning and developing new skills all the time. In addition, all areas of development are intertwined. Children do not learn motor skills in isolation of cognitive or communication skills in isolation. As a child learns to crawl, he is also exploring his environment (cognitive). He may also be responding to communication from mom as she says “come here.” Each routine a child participates in allows for opportunities for growth across all areas of development.

One of the seven key principles of natural environment services is that the family’s priorities are best addressed by a single, primary provider who has support from a team and community resources. In the PSP model, one primary provider works with the family and child on a regular, ongoing basis. Other disciplinary providers who are needed support the primary provider through consultation in team meetings or during sessions with the family and primary provider. Because routines involve skills across all developmental areas, it is unlikely that a single provider would address an isolated area of development when embedding strategies into the routine. For example, the list below describes a few of the developmental skills that children are learning during the bath time routine.

Gross Motor—Practicing independent sitting

Cognition—Learning about the properties of water, color, movement, temperature, space, etc.

Fine Motor—Practicing reaching and grasping, building arm strength through splashing, pushing through water,

Self-care—Washing self

Communication—Learning body parts when caregiver is washing different areas

Social—Reciprocating interaction while playing with sibling or caregiver

Using routines-based intervention, the primary provider addresses all areas of development within daily routines. Other providers are used as consultants. For example, a developmental specialist looking at a child’s bath time routine might be very comfortable providing ideas about social games, water play, and communication but may want to consult with a physical therapist on the team about adaptive seating in the bath tub. Or, if the primary provider was a physical therapist, she may be very comfortable giving strategies related to adaptive seating, water play, and social games, but may need to consult with a speech-language pathologist for ideas about increasing the child’s communication with mom. The primary provider may change over time (as the family’s concerns move more toward communication, the PT may no longer be the appropriate primary provider).

There are many benefits to the PSP model. Having one provider visit on a regular basis means the parent can focus on developing trust and rapport with one person. This model also encourages teaming, thereby increasing coordination of services. Gaps in communication (OT says “I thought speech was addressing feeding all this time”) and service overlaps (PT and OT are both addressing sitting balance) are decreased. The model promotes consistent, collaborated service. The primary provider is aware of all strategies that have been offered or tried and is able to update the team on what is working or not working.

The PSP model is based on information about the way children and adults learn. It promotes communication between team members to help achieve IFSP outcomes and increase caregiver confidence and competence.

Why do you like this model? If you have concerns about the model tell us why? What evidence is available that supports or refutes any service delivery model?

For more information:

Shelden ML & Rush DD (2013). The Early Intervention Teaming Handbook The primary service provider approach. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Woods J (2004). Enhancing services in natural environments. NECTAC Conference Call. retrieved on March 21, 2013 from: http://ectacenter.org/~calls/2004/partcsettings/woods.asp.

Workgroup on Principles and Practices in Natural Environments (February, 2008) Seven key principles: Looks like/doesn’t look like. OSEP TA Community of Practice-Part C Settings. http://www.nectac.org/topics/families/families.asp

– Jamie Holloway

Walkers, Jumpers, Exersaucers: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

Infant devices such as walkers, jumpers, and exersaucers are a frequent topic of concern in early intervention. These devices are widely marketed as helping promote a baby’s development and parents often feel they have to have them in order to meet their child’s needs. Additionally, some babies really seem to enjoy the time they spend in their devices. Research on the safety of these devices as well as on their effects on development, however, has not been as positive.

Walkers were originally developed to provide a means of mobility for exploration before a child learns to walk. DiLillo, Damashek, and Peterson (2001) found that parents use walkers and exersaucers for entertainment, perceived developmental benefit, and easy availability.

Concerns have arisen regarding the safety of these devices. Injuries have been reported related to the device itself such as pinching fingers and toes in device hardware and injuries caused because the child is more mobile. Increased mobility in these devices has led to burns when a child can maneuver close to a hot stove, poisonings when a child can bring themselves closer to cabinet sinks and other storage areas, and falls down stairs when a child gets too close to the edge (AAP 2001). Mandatory standards that were implemented in 1971 addressed the incidence of pinch injuries and, as a result, those injuries have decreased. Voluntary standards to address tip overs and falls were implemented in 1996, thus these injuries have decreased also.

However, providers should be aware that many families purchase these expensive devices from second-hand stores or receive them handed down from family members or friends and therefore, a provider cannot assume that the walker a child is using meets safety standards. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends against the use of walkers entirely due to questions around the safety of the devices. The AAP recommends that when families choose to use a device, they should select one that does not roll (an exersaucer), however, they caution that data on injuries with these devices are not yet available.

Safety concerns have also been observed with jumper devices that hang over doorways. Concerns related to falls are common. There have also been incidents in which children gained too much momentum and swung into door frames. Generally, devices that remain stationary are recommended over the jumpers over doorways.

The infamous Bumbo® seat has been recalled several times for safety modifications. Children have been able to tip out of the Bumbo® leading to injuries. The current recommendation is that the parent or caregiver supervise the child in the Bumbo® at all times. Also, children should only be placed in a Bumbo on the floor. They should never be placed in the Bumbo ®on top of a counter, couch, or other surface.

The impact of these devices on a baby’s development is also concerning. Siegel and Burton 1999 found that babies who spent time in walkers sat, crawled, and walked later than the control group that did not use the devices. In addition, the babies in the walker group scored lower on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-Mental and Motor, indicating that the devices may not have the positive impact on cognitive development as once thought. Another study (Kauffman & Ridenour, 1977) showed that children who spent time in walkers were more likely to use abnormal patterns of movement such as tiptoe walking when first learning to walk. However, there are other studies that indicate that the use of walkers provide a child a means of independent mobility that promotes cognitive development through independent environmental exploration (Kermoian &Campos).

The best place for a baby to learn to move their body is on the floor. There, the baby can learn to use his or her own muscles to initiate movement. Seats that help support a baby in these devices do not require the muscles to work as hard and often place the baby’s hips in a position of excessive external rotation and abduction. In addition, when babies spend less time on the floor, they lose opportunities to perform skills such as crawling that develop trunk and upper body strength.

When families ask if it is ok to use these devices, always make sure they are aware of the safety concerns around the particular device they are using. It is best for the baby to play on the floor, but if a family’s routines indicate a device is necessary, it should be used in moderation. Parents should also be cautioned about the amount of time a child spends in a seating device such as an infant carrier or bouncer chair as these devices also inhibit a baby’s movement and can impede development. A general rule of thumb is that no more than 15-20 minutes of an infant’s day should be spent in infant devices. What explanation have you used to help parents understand this issue?

For more information:

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2001). Injuries associated with infant walkers. Pediatrics, 108(3), 790-792. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/10J8/3/790.full

Kermoian R. & Campos JJ. (1988). Locomotor experience: a facilitator of spatial cognitive development. Child Development, 59: 908-917.

DiLillo, D., Damashek, A., Peterson, L. (2001). Maternal use of baby walkers with young children: recent trends and possible alternatives. Injury Prevention, 7, 223-227.

Kauffman, I.B., Ridenour M. (1977). Influence of an infant walker on onset and quality of walking pattern of locomotion: an electromyographic investigation. Percept Mot Skills, 45, 1323–1329.

Siegel, A.C., Burton, R.V. (1999). Effects of baby walkers on motor and mental development in human infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 20,355–361.

— Jamie Holloway

What does Natural Environments Really Mean?

IDEA defines the natural environment as “the home and community settings in which children without disabilities participate.” In other words, a natural environment is anywhere a child would go in her regular day whether or not she had a disability. Providers often think of natural environments as home or childcare, but the grocery store, park, library, or shopping mall are also good examples of natural environments. When IDEA was first implemented the makers of the law and the regulations that guide the law’s implementation meant for natural environments to mean more than location.

Delivering services and supports in an environment means that we must consider environment as the “the aggregate of social and cultural conditions that influence the life of an individual or community.” (Webster). Thus our services and supports to the families we serve must take into account all the things that influence the life of an individual:

- their social interactions and expectations,

- their cultural influences and priorities, and

- the routines and activities that are accomplished throughout the day.

Intervention planning considers these elements by partnering with families to determine appropriate and meaningful learning opportunities that reflect the family’s life style, priorities, concerns, and resources.

Two key components that are often missed in discussions about services in the natural environment are the concept of naturally occurring learning opportunities and the goal of participation in family routines. Children learn best through meaningful interaction and engagement within a familiar context, such as daily routines. Naturally occurring learning opportunities are the experiences that happen throughout a child’s day that allow for learning to occur in a natural, familiar context. Embedding strategies into naturally occurring learning opportunities increases opportunities for practice and, thus, maximizes learning. In addition, natural environment services focus on participation rather than the remediation of deficits. Increasing participation in daily routines increases the child’s engagement and interaction, which serves to help maximize learning.

Consider the following two scenarios. The IFSP team has written an outcome for a child to begin to identify colors. In order to meet this outcome, the provider sees the child at home. During the session, the provider sets up a small table and uses little animal figures to help the child identify colors. After the animal game, the provider and child play a special iPad game that uses sounds and animation to learn colors. The child’s older sister becomes very interested in the iPad, so the provider allows her to join in so the younger child will learn to take turns during play. At the end of the session, the provider tells the mother that they can play similar games using the toys in his bedroom.

In the second scenario, the provider meets the mother and child at the grocery store. The mother has been very distracted during sessions lately and mentioned having “so much to do next week” several times during the last session. The provider agreed to meet mom at the grocery store around the corner from the child’s home. As they walked through the produce section, the provider and mother talked about ways to help the child learn colors. The provider suggested that mom pick up two vegetables (carrots and cucumbers) and ask the child to point to the one that is green. They repeated this several more times as the mother gathered the vegetables for that night’s dinner salad. As they traveled to the cereal aisle, the provider asked the mom if she could think of a game to play on that aisle. Mom looked at her shopping list and saw “Cheerios,” so she asked her child to point to the yellow box. They continued to repeat similar strategies on different aisles throughout the session. As they were leaving the provider reminded mom that they can play similar games at home as she puts the groceries away.

Both scenarios address the IFSP outcome of learning colors. But, which of these two scenarios is reflective of true NE service? The first scenario takes place at the home and includes a developmentally appropriate game to teach the child colors. The provider uses family involvement by incorporating the sister and gives mom an activity to work on over the next week. The problem with this scenario is that it is unlikely to occur naturally. It is unlikely the toddler will sit at a small table on his own to participate in a learning game. In addition, the provider will take the animal figures and iPad with her when she leaves and the child will wait a full week before he sees those items again. The provider did give the mom an activity to work on, but it wasn’t in a naturally occurring way either. This scenario also does not address participation in family routines. How does this activity help the family’s daily life?

The second scenario takes place at the grocery store because mom’s schedule was too busy for the session to occur at home. The provider worked with the mom to identify and deliver strategies to help the child learn the colors. The mom is able to practice and gains confidence throughout the session, making it more likely that she will repeat the activity on the next grocery trip. Because grocery shopping is something this family does often, this scenario will occur again naturally and, from the sound of it, frequently. The provider also suggested a way to continue the learning activity when the family gets home. In addition, the mother and provider worked together to come up with strategies. Most of the intervention occurred through interactions between the child and mother. The provider used her expertise and knowledge of development to guide the mother to a developmentally appropriate game to learn colors. Lastly, the child was able to participate in the grocery shopping routine. He wasn’t just along for the ride as mom hurried through her day. He was actively engaged in the activity and the learning opportunities were increased.

What are some methods you have used to identify Naturally Occurring Learning Opportunities (NOLO) with the families you serve?

Listed below are some resources that are helpful in identifying Naturally Occurring Learning Opportunities:

FIPP CASETools: Checklists for Promoting Parent-Mediated Everyday Learning Opportunities—this can be downloaded from FIPP. It is a structured way to help providers identify with families NOLO. There is also an article about this in CASEinPoint by Dunst and Swanson. http://www.fipp.org/Collateral/casetools/casetools_vol2_no1.pdf

The ECTA center has several helpful resources to explain more about what contemporary early intervention practice considers intervention in the natural environment. http://ectacenter.org/~pdfs/topics/families/Principles_LooksLike_DoesntLookLike3_11_08.pdf

- Key Principles and Practices for Providing Early Intervention Services in Natural Environments:

o Mission and Key Principles for Providing Early Intervention Services in Natural Environments

o Seven Key Principles: Looks Like/Doesn’t Look like

o Agreed upon Practices for Providing Early Intervention Services in Natural Environments

McWilliam RA (2000). It’s only natural to have early intervention in the environments where it’s needed. Young Exceptional Children Monograph Series No 2: Natural Environments and Inclusion, 17-26.

Woods J (2004). Enhancing services in natural environments. NECTAC Conference Call. retrieved on August 30, 2013 from: http://ectacenter.org/~calls/2004/partcsettings/woods.asp.

— Jamie Holloway

Taping Tots: Using Kinesiotape in Early Intervention

Kinesiotape’s popularity is increasing with therapists, athletes, and the general public. Kinesiotape was once known only to orthopedic physical therapists who applied the tape skillfully for specific uses it is now available to the general public at any running or sports store. There are many on-line resources such as YouTube videos available demonstrating the uses and application of kinesiotape to solve everything from shin splints to tempomandibular joint pain. Although popular the use of kinesiotape in adults and athletes has not been proven to be effective. 1 The use of kinesiotape with children, especially those with developmental disabilities or delays has not even been studied.

So is there a case to use kinesiotape in EI?

Kinesiotape is often used to promote alignment either with children with torticollis or decreased abdominal control. The research, based on few small population studies, indicates that kinesiotape may be beneficial for use with children with torticollis to reduce the asymmetrical position of their head 2. The tape can be applied to relax (or inhibit) the tight sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). Alternately tape can be applied to encourage contraction (or facilitation) of the weaker or lengthened opposite lateral flexor muscles.

Applying tape to young children can be challenging for parents and therapists, for that reason it is often used as an adjunct to an intervention, applied by the therapist with instruction to the family on removing it. When used for children whose muscles have adequate range of motion the “facilitation” technique can help cue kids through tactile pressure to activate the SCM. The tape serves as a tactile reminder to maintain proper alignment.

Example of facilitating the lengthened SCM: image from http://ot4kids.co.uk/kinesio-taping/benefits

Children with decreased abdominal control and decreased muscular endurance, are more likely to have trunk deviations affecting their sitting balance and overall stability. While there have not been any large pediatric population studies examining the benefit of using kinesiotape for abdominal control it is commonly applied by therapists. Studies that have examined the effect of kinesiotape on sitting posture in children with cerebral palsy have been inconclusive. Ssimssek and Mazzone found improvements in sitting posture and improved arm movements3,4, although Footer5 found no benefit. Children need adequate abdominal strength and need to maintain the abdominal contraction to independently roll, sit, crawl and walk efficiently. Kinesiotape can act as a tactile reminder to contract the abdominals and prevent any deviations in trunk alignment. Taping techniques to encourage use of the abdominals is easily replicated by parents once they are instructed.

The use of kinesiotape in young children demands research and clear data collection from those of us who are using it in practice.

Do you use kinesiotape in your practice?

What techniques do you use or what do you find beneficial or useless about it?

How are you collecting data to determine its effectiveness?

References

- Morris D, Jones D, Ryan H, Ryan CG. (2012). The clinical effects of Kinesio(®) Tex taping: A systematic review. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 259-270.

- Ohman A. The immediate effect of kinesiology taping on muscular imbalance for infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 4:504-508.

- ŞŞimşşek TT, Türkücüoğğlu B, Çokal N, Üstünbaşş G, and ŞŞimşşek İE. (2011). The effects of Kinesio® taping on sitting posture, functional independence and gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33 : 2058-2063.

- Mazzone S, Serafini A, Iosa M, Aliberti MN, Gobbetti T, Paolucci S, Morelli D. (2011). Functional taping applied to upper limb of children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: a pilot study, 42(6):249-53.

- Footer CB. (2006). The effects of therapeutic taping on gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 18: 245-52.

– Erin Wentzell

Tummy Time: It’s More Than Just a Place

We have all said it and written it a million times: Your baby needs Tummy Time every day! But do we ever take the time to explain what that means or why it’s important? Maybe if we took the time to explain to caregivers the benefits of Tummy Time, they would understand the need to create opportunities to promote Tummy Time.

What are the benefits of Tummy Time and what are the essential suggestions we should be giving caregivers to promote the use of Tummy Time, throughout the day?

Tummy Time can be more than just a position, it can be an activity to engage with a child and develop necessary strength and developmental skills. When Tummy Time incorporates active play it gives parents the opportunity to work on head control, eye contact, shoulder girdle strength, vocalizations, engagement, and social interaction. Playing while on the tummy develops initial upper extremity weight shifting skills, strength of the upper back and trunk muscles, postural control, and proprioception. It also helps the baby to dissociate his head from his trunk and use the muscles around his eyes. Although initially Tummy Time is a passive position, we must encourage caregivers to actively engage with the infant. Suggest to the caregiver to sing songs while the child is laying on their chest in the morning in bed or play peek-a-boo with a blanket on the floor or knock over cups or any other fun age-appropriate activity that engages the child while on their tummy.

Check out these sites for more ideas about Tummy Time. Remember to personalize these guidelines to include active play games for the caregiver and the child.

- Children’s Hospital of Atlanta: Tummy Time Tools (in 7 languages) http://www.choa.org/childrens-hospital-services/orthopaedics/programs-services/orthotics-and-prosthetics/Tummy-Time-tools

- Pathways.org: 5 Essential Tummy Time Moves (in Spanish and English) http://pathways.org/awareness/healthcare-professionals/talking-about-Tummy-Time#.Uf52HpLOuuk

- Check out the video for more ideas of Tummy Time Moves: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3rCtW9DMD4

—

Erin Wentzell PT, DPT, PCS